domingo, 31 de dezembro de 2017

sábado, 30 de dezembro de 2017

A PATH LESS TAKEN TO THE PEAK OF THE MATH WORLD

Outra das matérias mais lidas do site Quanta Magazine em 2017. De certa forma, me identifiquei um pouco com a história do June Huh.

* * *

June Huh thought he had no talent for math until a chance meeting with a legendary mind. A decade later, his unorthodox approach to mathematical thinking has led to major breakthroughs.

June Huh at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, N.J.

On a warm morning in early spring, June Huh walked across the campus of Princeton University. His destination was McDonnell Hall, where he was scheduled to teach, and he wasn’t quite sure how to get there. Huh is a member of the rarefied Institute for Advanced Study, which lies adjacent to Princeton’s campus. As a member of IAS, Huh has no obligation to teach, but he’d volunteered to give an advanced undergraduate math course on a topic called commutative algebra. When I asked him why, he replied, “When you teach, you do something useful. When you do research, most days you don’t.”

We arrived at Huh’s classroom a few minutes before class was scheduled to begin. Inside, nine students sat in loose rows. One slept with his head down on the table. Huh took a position in a front corner of the room and removed several pages of crumpled notes from his backpack. Then, with no fanfare, he picked up where he’d left off the previous week. Over the next 80 minutes he walked students through a proof of a theorem by the German mathematician David Hilbert that stands as one of the most important breakthroughs in 20th-century mathematics.

Commutative algebra is taught at the undergraduate level at only a few universities, but it is offered routinely at Princeton, which each year enrolls a handful of the most promising young math minds in the world. Even by that standard, Huh says the students in his class that morning were unusually talented. One of them, sitting that morning in the front row, is the only person ever to have won five consecutive gold medals at the International Mathematical Olympiad.

Huh’s math career began with much less acclaim. A bad score on an elementary school test convinced him that he was not very good at math. As a teenager he dreamed of becoming a poet. He didn’t major in math, and when he finally applied to graduate school, he was rejected by every university save one.

Nine years later, at the age of 34, Huh is at the pinnacle of the math world. He is best known for his proof, with the mathematicians Eric Katz and Karim Adiprasito, of a long-standing problem called the Rota conjecture.

Even more remarkable than the proof itself is the manner in which Huh and his collaborators achieved it — by finding a way to reinterpret ideas from one area of mathematics in another where they didn’t seem to belong. This past spring IAS offered Huh a long-term fellowship, a position that has been extended to only three young mathematicians before. Two of them (Vladimir Voevodsky and Ngô Bảo Châu) went on to win the Fields Medal, the highest honor in mathematics.

That Huh would achieve this status after starting mathematics so late is almost as improbable as if he had picked up a tennis racket at 18 and won Wimbledon at 20. It’s the kind of out-of-nowhere journey that simply doesn’t happen in mathematics today, where it usually takes years of specialized training even to be in a position to make new discoveries. Yet it would be a mistake to see Huh’s breakthroughs as having come in spite of his unorthodox beginning. In many ways they’re a product of his unique history — a direct result of his chance encounter, in his last year of college, with a legendary mathematician who somehow recognized a gift in Huh that Huh had never perceived himself.

We arrived at Huh’s classroom a few minutes before class was scheduled to begin. Inside, nine students sat in loose rows. One slept with his head down on the table. Huh took a position in a front corner of the room and removed several pages of crumpled notes from his backpack. Then, with no fanfare, he picked up where he’d left off the previous week. Over the next 80 minutes he walked students through a proof of a theorem by the German mathematician David Hilbert that stands as one of the most important breakthroughs in 20th-century mathematics.

Commutative algebra is taught at the undergraduate level at only a few universities, but it is offered routinely at Princeton, which each year enrolls a handful of the most promising young math minds in the world. Even by that standard, Huh says the students in his class that morning were unusually talented. One of them, sitting that morning in the front row, is the only person ever to have won five consecutive gold medals at the International Mathematical Olympiad.

Huh’s math career began with much less acclaim. A bad score on an elementary school test convinced him that he was not very good at math. As a teenager he dreamed of becoming a poet. He didn’t major in math, and when he finally applied to graduate school, he was rejected by every university save one.

Nine years later, at the age of 34, Huh is at the pinnacle of the math world. He is best known for his proof, with the mathematicians Eric Katz and Karim Adiprasito, of a long-standing problem called the Rota conjecture.

Even more remarkable than the proof itself is the manner in which Huh and his collaborators achieved it — by finding a way to reinterpret ideas from one area of mathematics in another where they didn’t seem to belong. This past spring IAS offered Huh a long-term fellowship, a position that has been extended to only three young mathematicians before. Two of them (Vladimir Voevodsky and Ngô Bảo Châu) went on to win the Fields Medal, the highest honor in mathematics.

That Huh would achieve this status after starting mathematics so late is almost as improbable as if he had picked up a tennis racket at 18 and won Wimbledon at 20. It’s the kind of out-of-nowhere journey that simply doesn’t happen in mathematics today, where it usually takes years of specialized training even to be in a position to make new discoveries. Yet it would be a mistake to see Huh’s breakthroughs as having come in spite of his unorthodox beginning. In many ways they’re a product of his unique history — a direct result of his chance encounter, in his last year of college, with a legendary mathematician who somehow recognized a gift in Huh that Huh had never perceived himself.

Inside Huh’s office at the IAS. (Jean Sweep for Quanta Magazine)

The Accidental Apprentice

Huh was born in 1983 in California, where his parents were attending graduate school. They moved back to Seoul, South Korea, when he was two. There, his father taught statistics and his mother became one of the first professors of Russian literature in South Korea since the onset of the Cold War.

After that bad math test in elementary school, Huh says he adopted a defensive attitude toward the subject: He didn’t think he was good at math, so he decided to regard it as a barren pursuit of one logically necessary statement piled atop another. As a teenager he took to poetry instead, viewing it as a realm of true creative expression. “I knew I was smart, but I couldn’t demonstrate that with my grades, so I started to write poetry,” Huh said.

Huh wrote many poems and a couple of novellas, mostly about his own experiences as a teenager. None were ever published. By the time he enrolled at Seoul National University in 2002, he had concluded that he couldn’t make a living as a poet, so he decided to become a science journalist instead. He majored in astronomy and physics, in perhaps an unconscious nod to his latent analytic abilities.

When Huh was 24 and in his last year of college, the famed Japanese mathematician Heisuke Hironaka came to Seoul National as a visiting professor. Hironaka was in his mid-70s at the time and was a full-fledged celebrity in Japan and South Korea. He’d won the Fields Medal in 1970 and later wrote a best-selling memoir called The Joy of Learning, which a generation of Korean and Japanese parents had given their kids in the hope of nurturing the next great mathematician. At Seoul National, he taught a yearlong lecture course in a broad area of mathematics called algebraic geometry. Huh attended, thinking Hironaka might become his first subject as a journalist.

Initially Huh was among more than 100 students, including many math majors, but within a few weeks enrollment had dwindled to a handful. Huh imagines other students quit because they found Hironaka’s lectures incomprehensible. He says he persisted because he had different expectations about what he might get out of the course.

“The math students dropped out because they could not understand anything. Of course, I didn’t understand anything either, but non-math students have a different standard of what it means to understand something,” Huh said. “I did understand some of the simple examples he showed in classes, and that was good enough for me.”

After class Huh would make a point of talking to Hironaka, and the two soon began having lunch together. Hironaka remembers Huh’s initiative. “I didn’t reject students, but I didn’t always look for students, and he was just coming to me,” Hironaka recalled.

Huh tried to use these lunches to ask Hironaka questions about himself, but the conversation kept coming back to math. When it did, Huh tried not to give away how little he knew. “Somehow I was very good at pretending to understand what he was saying,” Huh said. Indeed, Hironaka doesn’t remember ever being aware of his would-be pupil’s lack of formal training. “It’s not anything I have a strong memory of. He was quite impressive to me,” he said.

As the lunchtime conversations continued, their relationship grew. Huh graduated, and Hironaka stayed on at Seoul National for two more years. During that period, Huh began working on a master’s degree in mathematics, mainly under Hironaka’s direction. The two were almost always together. Hironaka would make occasional trips back home to Japan and Huh would go with him, carrying his bag through airports and even staying with Hironaka and his wife in their Kyoto apartment.

“I asked him if he wanted a hotel and he said he’s not a hotel man. That’s what he said. So he stayed in one corner of my apartment,” Hironaka said.

Heisuke Hironaka, Huh and Nayoung Kim (now Huh’s wife) celebrating Hironaka’s 78th birthday in 2009. (Gayoung Cho)

In Kyoto and Seoul, Hironaka and Huh would go out to eat or take long walks, during which Hironaka would stop to photograph flowers. They became friends. “I liked him and he liked me, so we had that kind of nonmathematical chatting,” Hironaka said.

Meanwhile, Hironaka continued to tutor Huh, working from concrete examples that Huh could understand rather than introducing him directly to general theories that might have been more than Huh could grasp. In particular, Hironaka taught Huh the nuances of singularity theory, the field where Hironaka had achieved his most famous results. Hironaka had also been trying for decades to find a proof of a major open problem — what’s called the resolution of singularities in characteristic p. “It was a lifetime project for him, and that was principally what we talked about,” Huh said. “Apparently he wanted me to continue this work.”

In 2009, at Hironaka’s urging, Huh applied to a dozen or so graduate schools in the U.S. His qualifications were slight: He hadn’t majored in math, he’d taken few graduate-level classes, and his performance in those classes had been unspectacular. His case for admission rested largely on a recommendation from Hironaka. Most admissions committees were unimpressed. Huh got rejected at every school but one, the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, where he enrolled in the fall of 2009.

(O restante da matéria é mais focado na pesquisa de Huh, com uma abordagem um tanto mais técnica, conceitos matemáticos avançados etc.).

TO LIVE YOUR BEST LIFE, DO MATHEMATICS

Uma história de vida extremamente emocionante e inspiradora. Não é à toa que foi uma das matérias mais lidas do site Quanta Magazine em 2017.

* * *

The ancient Greeks argued that the best life was filled with beauty, truth, justice, play and love. The mathematician Francis Su knows just where to find them.

Mark Skovorodko for Quanta Magazine

Math conferences don’t usually feature standing ovations, but Francis Su received one last month in Atlanta. Su, a mathematician at Harvey Mudd College in California and the outgoing president of the Mathematical Association of America (MAA), delivered an emotional farewell address at the Joint Mathematics Meetings of the MAA and the American Mathematical Society in which he challenged the mathematical community to be more inclusive.

Su opened his talk with the story of Christopher, an inmate serving a long sentence for armed robbery who had begun to teach himself math from textbooks he had ordered. After seven years in prison, during which he studied algebra, trigonometry, geometry and calculus, he wrote to Su asking for advice on how to continue his work. After Su told this story, he asked the packed ballroom at the Marriott Marquis, his voice breaking: “When you think of who does mathematics, do you think of Christopher?”

Su grew up in Texas, the son of Chinese parents, in a town that was predominantly white and Latino. He spoke of trying hard to “act white” as a kid. He went to college at the University of Texas, Austin, then to graduate school at Harvard University. In 2015 he became the first person of color to lead the MAA. In his talk he framed mathematics as a pursuit uniquely suited to the achievement of human flourishing, a concept the ancient Greeks called eudaimonia, or a life composed of all the highest goods. Su talked of five basic human desires that are met through the pursuit of mathematics: play, beauty, truth, justice and love.

If mathematics is a medium for human flourishing, it stands to reason that everyone should have a chance to participate in it. But in his talk Su identified what he views as structural barriers in the mathematical community that dictate who gets the opportunity to succeed in the field — from the requirements attached to graduate school admissions to implicit assumptions about who looks the part of a budding mathematician.

When Su finished his talk, the audience rose to its feet and applauded, and many of his fellow mathematicians came up to him afterward to say he had made them cry. A few hours later Quanta Magazine sat down with Su in a quiet room on a lower level of the hotel and asked him why he feels so moved by the experiences of people who find themselves pushed away from math. An edited and condensed version of that conversation and a follow-up conversation follows.

Su opened his talk with the story of Christopher, an inmate serving a long sentence for armed robbery who had begun to teach himself math from textbooks he had ordered. After seven years in prison, during which he studied algebra, trigonometry, geometry and calculus, he wrote to Su asking for advice on how to continue his work. After Su told this story, he asked the packed ballroom at the Marriott Marquis, his voice breaking: “When you think of who does mathematics, do you think of Christopher?”

Su grew up in Texas, the son of Chinese parents, in a town that was predominantly white and Latino. He spoke of trying hard to “act white” as a kid. He went to college at the University of Texas, Austin, then to graduate school at Harvard University. In 2015 he became the first person of color to lead the MAA. In his talk he framed mathematics as a pursuit uniquely suited to the achievement of human flourishing, a concept the ancient Greeks called eudaimonia, or a life composed of all the highest goods. Su talked of five basic human desires that are met through the pursuit of mathematics: play, beauty, truth, justice and love.

If mathematics is a medium for human flourishing, it stands to reason that everyone should have a chance to participate in it. But in his talk Su identified what he views as structural barriers in the mathematical community that dictate who gets the opportunity to succeed in the field — from the requirements attached to graduate school admissions to implicit assumptions about who looks the part of a budding mathematician.

When Su finished his talk, the audience rose to its feet and applauded, and many of his fellow mathematicians came up to him afterward to say he had made them cry. A few hours later Quanta Magazine sat down with Su in a quiet room on a lower level of the hotel and asked him why he feels so moved by the experiences of people who find themselves pushed away from math. An edited and condensed version of that conversation and a follow-up conversation follows.

QUANTA MAGAZINE: The title of your talk was “Mathematics for Human Flourishing.” Flourishing is a big idea — what do you have in mind by it?

FRANCIS SU: When I think of human flourishing, I’m thinking of something close to Aristotle’s definition, which is activity in accordance with virtue. For instance, each of the basic desires that I mentioned in my talk is a mark of flourishing. If you have a playful mind or a playful spirit, or you’re seeking truth, or pursuing beauty, or fighting for justice, or loving another human being — these are activities that line up with certain virtues. Maybe a more modern way of thinking about it is living up to your potential, in some sense, though I wouldn’t just limit it to that. If I am loving somebody well, that’s living up to a certain potential that I have to be able to love somebody well.

And how does mathematics promote human flourishing?

It builds skills that allow people to do things they might otherwise not have been able to do or experience. If I learn mathematics and I become a better thinker, I develop perseverance, because I know what it’s like to wrestle with a hard problem, and I develop hopefulness that I will actually solve these problems. And some people experience a kind of transcendent wonder that they’re seeing something true about the universe. That’s a source of joy and flourishing.

Math helps us do these things. And when we talk about teaching mathematics, sometimes we forget these larger virtues that we are seeking to cultivate in our students. Teaching mathematics shouldn’t be about sending everybody to a Ph.D. program. That’s a very narrow view of what it means to do mathematics. It shouldn’t mean just teaching people a bunch of facts. That’s also a very narrow view of what mathematics is. What we’re really doing is training habits of mind, and those habits of mind allow people to flourish no matter what profession they go into.

Several times in your talk you quoted Simone Weil, the French philosopher (and sibling of the famed mathematician André Weil), who wrote, “Every being cries out silently to be read differently.” Why did you choose that quote?

I chose it because it says in a very succinct way what the problem is, what causes injustice — we judge, and we don’t judge correctly. So “read” means “judged,” of course. We read people differently than they actually are.

And how does that apply to the math community?

We do this in lots of different ways. I think part of it is that we have a picture of who actually can succeed in math. Some of that picture has been developed because the only examples we’ve seen so far are people who come from particular backgrounds. We’re not used to, for instance, seeing African-Americans at a math conference, although it’s become more and more common.

We’re not used to seeing kids from lower socioeconomic backgrounds in college or grad school. So what I was trying to say is: If we’re looking for talent, why are we choosing for background? If we really want to have a more diverse set of people in mathematical sciences, we have to take into account the structural barriers that make it hard for people from disadvantaged backgrounds to succeed in math.

We’ve been hearing more about how these kinds of educational barriers arise in primary and secondary school. Do you argue that they arise in undergraduate and graduate programs as well?

That’s right. At every stage we’re losing people. So if you look at some of the studies people are doing now about people who take Calculus 1, and how many of them go on to take Calculus 2, you’ll find basically that we’re losing women and minorities at these critical junctures. This happens for reasons that we can only speculate about. But I’m sure some of it has to do with people in these groups not seeing themselves as belonging in math, possibly because of a negative culture and an unwelcome climate, or because of things that professors or other students are doing to discourage people from continuing.

The obvious problem with this attrition is that when mathematics draws from a smaller pool, we end up with fewer talented mathematicians. But you emphasized in your speech that denying people math is actually denying them an opportunity to flourish.

Math can contribute in a broad way to every person’s life whether that person actually becomes a mathematician or not. The goal of broadly getting people to appreciate math is not at odds with bringing more people into deep mathematics. Connect with people in a deep way and you’re going to draw more people into mathematics. Some of them, more of them, are going to go to graduate school, and that will necessarily happen if you address some of these deep desires — for love, truth, beauty, justice, play. If you address some of these deep themes you’re going to get more people and a more diverse set of people in deep mathematics.

Some of those desires are easier to relate to math than others. I think people have a somewhat intuitive sense of how a desire for truth or beauty might be realized through math. But you spent a lot of your talk on justice. How does that relate to mathematics?

Justice is a desire that people have, and so it leads to a certain virtue which is to become a just person, somebody who cares about fighting for things that defend basic human dignity. I spent the most time discussing justice in my talk mainly because I feel that our mathematics community can do better; we can become more just. I see a lot of ways in which we can do better and become more virtuous as a community.

Being a mathematician in some ways allows us to see things more for what they are. When people learn not to overgeneralize their arguments, they’re going to be very careful not to think that if you’re poor you’re necessarily uneducated or vice versa. Having a mathematical background certainly helps people to be less governed by their biases.

You’ve been a successful research mathematician, yet you teach at a small college, Harvey Mudd, that doesn’t have a graduate school. That’s kind of unusual. Was there a point where you decided you’d prefer to work at a liberal arts college rather than a big research university?

When I was in graduate school at Harvard I realized I loved teaching, and I remember one of my professors from college telling me that the teaching was better at small liberal arts colleges. So when I was on the job market I started looking at those colleges. I was interested in the research track and willing to do that, but I was also very attracted to the liberal arts environment. I chose to go and I love it; I couldn’t see myself being anywhere else.

And how do you think working at a liberal arts college shapes the way you look at the mathematics community today?

I think one of the things I didn’t address in the talk, but almost did, is the divide in the community between research universities and liberal arts colleges. There is a cultural divide, and the research universities are in some sense the dominant culture because all of us with Ph.D.s come through research universities. And there’s the whole pattern of the dominant culture being completely unaware of what’s going on at the liberal arts colleges. So people come up to me and say: “So, you’re at Harvey Mudd; are you happy there?” It’s almost like assuming I wouldn’t be. That happens all the time, so I find it a bit frustrating to feel like I have to say: “No, this is actually my dream job.”

What are the consequences of this cultural imbalance?

Well, the downsides are, for instance, that many of the people at research universities would never consider taking students from an undergraduate college. That’s the downside; they’re missing a lot of talent. So in many ways the issues are analogous to some of the racial issues that are going on.

I think professors at research universities often don’t realize that there are a lot of bright kids coming through the liberal arts colleges. What I’m addressing is the very common practice right now in certain graduate schools of only admitting people who’ve already had a full slate of graduate courses. In other words, they’re expecting undergraduates to have taken graduate courses before they even get considered. If you have that kind of structural situation, you are necessarily going to exclude a bunch of people who otherwise might be successful.

One barrier you mentioned in your talk arises when senior professors don’t teach introductory classes. Tell me about that.

I’m being a little provocative here as well. I think what that communicates is: “This is not an important enough segment of people for me to put my attention to.” I’m certainly not saying everybody who only teaches senior-level courses has this attitude, but I am saying there are a lot of people who think the math major is basically there for the benefit of students who are going to get a Ph.D. That’s a problem.

Su on the Harvey Mudd campus. (Mark Skovorodko for Quanta Magazine)

At the Joint Mathematics Meetings there were a number of prizes specifically for women, and a number of women gave invited talks. Has the math community made more progress on gender equality than on racial inclusiveness?

Definitely, racial inclusiveness has not come as far or as fast as gender inclusiveness. Currently about 27 percent of people with Ph.D.s, faculty members, are women, and about 30 percent of the ones who won awards in teaching and service are women. So we’re actually doing pretty well on that front. With our writing awards, which are awards for research and exposition — the fraction of women winning those awards is lower.

Can you look at the process by which gender equality has improved and draw any lessons from that about how to improve racial equality in math?

Many of the practices that work to encourage women in math also work for minorities. Part of the issue here is that there just aren’t that many minorities who come into college interested in doing STEM majors. So there’s something that happened at the secondary and primary school level, and it would help a lot if we could figure out what’s going on there.

You used the metaphor of a “secret menu” in Chinese restaurants. What did you mean by that?

If you go to an authentic restaurant in a big city in New York or California, if you are not Chinese they will give you a standard menu that has things in English and Chinese. But if you’re Chinese, they’ll give you a different menu. Often it’s a menu that is written completely in Chinese and has some additional options that aren’t on the standard menu. And I think that happens in the math community. If you talk to women and minorities they will often tell you they’ve had experiences where people discouraged them from going on, either because they don’t think a woman should be in math, or for other reasons. So I used the metaphor “secret menu” to mean: Do we have a secret menu? And who gets to look at it?

You told a story about a student who was counseled by a professor to choose a different major on the grounds that the student wasn’t good enough to stick with math. Is that common?

I think it’s common. Of course we don’t have any data, but I’ve certainly talked to enough people who’ve had those kinds of experiences to know that it’s very frequent and most of those people are women and minorities.

It’s been almost a month since you gave your speech, and it’s generated a lot of attention on the internet and among mathematicians. What kinds of responses have you received?

Most of the comments have come from people who are grateful to me for mentioning things that haven’t necessarily been discussed, but also for identifying some of the deep, underlying things that cause us to do what we do. I think a lot of people, especially women and minorities, have expressed to me how important it was for somebody to say that. We’ve been having discussions like this in smaller conversations, and a lot of time it’s preaching to the choir, and so having somebody say that in a big address at the national meeting I think felt important and helpful to them.

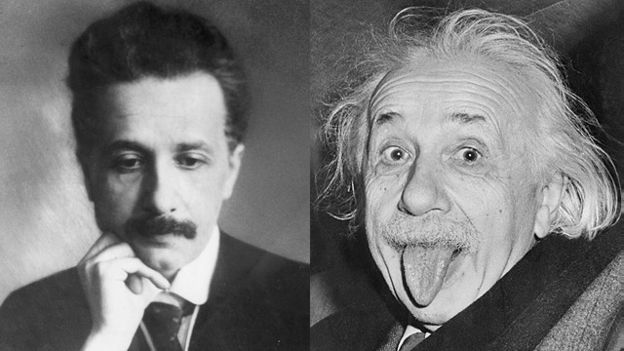

A FASE MENOS CONHECIDA DO CIENTISTA MAIS FAMOSO DO MUNDO

A equivalência entre a massa e a energia descrita por Einstein mudou a forma com que a ciência interpreta o mundo | Foto: Thinkstock

Nos anos 1920, Albert Einstein já havia criado a teoria quântica e resolvido a da relatividade. Ele então embarcou em sua última grande expedição pelos mistérios mais profundos da física, naquilo que se tornaria a realização incompleta de um sonho: a busca de uma teoria unificada que conectaria todas as forças da natureza em uma única equação mestra.

Esse é o Einstein que mais conhecemos, aquele que buscou resolver os enigmas mais obscuros do mundo.

Mas, ao mesmo tempo, ele tinha trabalhos paralelos.

Um deles era a invenção de um novo tipo de geladeira.

Sim, Einstein também foi um inventor. Esta nunca foi a parte principal de seu trabalho, mas ele a levava a sério.

No entanto, ainda parece um pouco estranho que o homem que nos deu a equação E = mc2 e mudou as noções da ciência sobre o tempo e o espaço tenha decidido criar um eletrodoméstico.

O caminho para a fama

Há um período da vida adulta de Einstein pouco conhecido | Foto: Getty Images

O que aconteceu com Einstein durante sua vida adulta, entre o jovem gênio e o senhor de cabelos brancos e língua de fora que conhecemos nas fotos? Perguntamos a Katy Price, professora da University Queen Mary de Londres, que pesquisou o período de celebridade emergente do físico na década de 1920.

"Nós realmente não pensamos muito sobre como o jovem Einstein se transformou no mais velho, e é nessa fase em que tudo está realmente mudando", diz ela.

"Em todo o mundo, se falava sobre a sensacional nova teoria do Universo. Uma manchete do [jornal] New York Times, por exemplo, dizia: 'Jazz no mundo científico'".

"Na imprensa, descreveram muito a sua aparência: a roupa que ele usava, seus cabelos, seus olhos...: 'Parece um homem afetuoso, é bom com crianças, toca violino'. Era uma tentativa de humanizar a pessoa que nos deu essa teoria matemática intensamente abstrata."

Mas tudo isso contrastava fortemente com o que estava acontecendo na sua Alemanha natal.

Turbulências

Pode-se imaginar que Einstein estivesse desfrutando do sucesso e da fama em seu auge.

Mas, na verdade, esse período de sua vida foi difícil, tanto na ciência como na vida privada e no seu país.

Relacionamento de Einstein com a segunda esposa, Elsa, não era pacífico | Foto: Getty Images

Ele já tinha se casado duas vezes, tinha vários casos amorosos e seu relacionamento com a segunda esposa, Elsa, claramente não era pacífico.

Uma parte da imprensa alemã também não era favorável ao cientista. Eles criticavam suas ideias internacionalistas, acusadas de antipatrióticas. E, desde os anos 1920, essa crítica já estava tingida de antissemitismo.

Em 1933, o jornal nazista Völkische Beobachter atacou abertamente suas teorias científicas por virem de um judeu.

"O exemplo mais importante da influência perigosa dos círculos judeus nos estudos da natureza vem do Sr. Einstein, com suas teorias matematicamente toscas que consistem em algum conhecimento antigo acrescido de incrementos arbitrários."

Einstein chegou a temer por sua vida.

"E com razão", diz Price.

"No New York Times, no meio da cobertura de suas palestras, há notícias de que, em Berlim, um líder antissemita foi multado por tentar organizar um complô para matar Einstein. Então, na verdade, alguns queriam matá-lo e outros queriam matar sua ciência."

Parceria para invenção

Em 1926, Einstein leu uma notícia no jornal sobre uma família que morreu após gases tóxicos escaparem de sua geladeira.

Essa triste história deve ter-lhe comovido, porque ele começou a fazer algo para tentar resolver o problema.

Talvez fosse porque ele queria se distrair; ou pode ter sido um reflexo de sua conhecida sensibilidade.

O fato é que Einstein conhecia uma pessoa que poderia ajudá-lo: um brilhante jovem formado na Universidade de Berlim chamado Leo Szilard.

Szilard era um especialista em termodinâmica, a ciência que descreve como o calor se move - e isso é o que faz uma geladeira funcionar.

E, bem, não se rejeita um pedido de parceira com Einstein, certo?

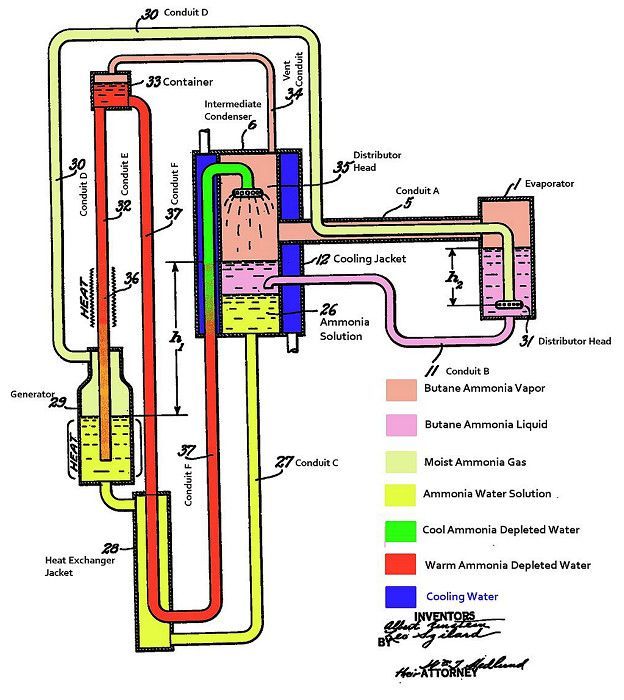

Um campo eletromagnético para a geladeira

Naquela época, geladeiras não eram muito comuns. Embora mais parecessem uma caixa-forte do que um eletrodoméstico, a princípio elas não eram muito diferentes das atuais.

Elas usam um fluido refrigerante para absorver o calor no interior do aparelho e liberá-lo - o fluido contrai, expande e circula através de um circuito de tubos.

Os refrigerantes, naquele tempo, eram gases tóxicos, com amônia e dióxido de enxofre em sua composição, por exemplo. Eles podiam escapar quanto algumas partes da geladeira, as partes móveis, se desgastavam.

Einstein e Szilard perceberam que os refrigeradores seriam mais seguros se houvesse menos partes móveis.

Einstein e Szilard desenvolveram um sistema de refrigeração com menos partes móveis

Eles se livraram da parte do circuito que condensava e evaporava o fluido e substituíram-no por uma bomba de compressão que projetaram, sem peças móveis.

Um campo eletromagnético permitia a movimentação do metal líquido - o mercúrio -, que atuava como um pistão para comprimir o gás.

Invenção barulhenta

Em 1927, a divisão de refrigeração da empresa sueca Electrolux comprou um dos pedidos de patente de Einstein e Szilard pelo valor de US$ 10 mil (cerca de R$ 33 mil; em valores atuais). A companhia alemã AEG fez o mesmo.

No entanto, a geladeira tinha seus problemas. Um deles era que a movimentação do mercúrio fazia muito barulho.

Mas, um por um, os problemas foram resolvidos e, em 1932, já havia vários protótipos promissores da geladeira Einstein-Szilard nos laboratórios da AEG.

No entanto, aconteceu uma catástrofe.

A República de Weimar (estabelecida na Alemanha após a Primeira Guerra Mundial) já havia atenuado uma hiperinflação insana no país no início da década de 1920, mas agora os efeitos da Grande Depressão de 1929 estavam desestabilizando o governo e os negócios.

Em meio ao caos e à instabilidade que alimentaram a eleição do governo nacional-socialista de Adolf Hitler, a AEG foi forçada a fechar suas pesquisas sobre refrigeração.

E com Einstein e Szilard exilados da Alemanha, os planos para lançar a nova geladeira foram interrompidos.

Quase sete décadas depois...

Embora o refrigerador cocriado por Einstein ainda tivesse o problema de não ter um fluido que não fosse tóxico para os seres humanos e nem para o meio ambiente, existem razões para que o projeto ainda seja atraente.

"O interesse para nós é que ele não tinha partes móveis", diz Malcolm McCulloch, um engenheiro da Universidade de Oxford que em 2008 construiu a engenhoca com base nos projetos dos cientistas.

"Isso é muito útil em lugares remotos onde não há pessoas qualificadas para fazer consertos manualmente. O segundo estímulo que achamos interessante é a possibilidade de usar o calor residual", explica.

"Além disso, uma das grandes vantagens para mim é que ela não precisa de eletricidade."

Outros problemas

É improvável que os dois físicos tenham ficado muito preocupados com o fracasso de sua geladeira. Já em 1932, eles tinham problemas mais importantes com os quais lidar.

Em 1934, Szilard patenteou o processo de reação em cadeia nuclear iniciada por nêutrons, que poderia permitir o uso de energia nuclear para diversos fins. Dois anos depois, em meio à tensão entre os países europeus, ele deu a patente ao almirantado britânico, o antigo responsável pela Marinha Real Britânica, para que ela permanecesse secreta.

Einstein se considerava pacifista, mas bomba atômica acabou entre os legados atribuídos a ele | Foto: Getty Images

Mas em 1938, a fissão nuclear do urânio, reação usada em usinas nucleares e na bomba atômica, foi descoberta na Alemanha.

Em agosto de 1939, um mês antes do início oficial da Segunda Guerra Mundial, Szilard e Einstein assinaram uma carta ao presidente dos Estados Unidos, Franklin D. Roosevelt, alertando que os alemães poderiam estar construindo uma bomba atômica e pedindo que o país investigasse.

A carta levou ao estabelecimento do Projeto Manhattan e ao lançamento das bombas nucleares sobre Hiroshima e Nagasaki, no Japão, em 1945.

Hoje em dia são as bombas nucleares, e não as geladeiras, que são consideradas parte do legado de Einstein.

A NON-PROGRAMMER’S APOLOGY (AARON SWARTZ)

In his classic A Mathematicians Apology, published 65 years ago, the great mathematician G. H. Hardy wrote that “A man who sets out to justify his existence and his activities” has only one real defense, namely that “I do what I do because it is the one and only thing that I can do at all well.” “I am not suggesting,” he added,

Reading such comments one cannot help but apply them to oneself, and so I did. Let us eschew humility for the sake of argument and suppose that I am a great programmer. By Hardy’s suggestion, the responsible thing for me to do would be to cultivate and use my talents in that field, to spend my life being a great programmer. And that, I have to say, is a prospect I look upon with no small amount of dread.

It was not always quite this way. For quite a while programming was basically my life. And then, somehow, I drifted away. At first it was small steps — discussing programming instead of doing it, then discussing things for programmers, and then discussing other topics altogether. By the time I reached the end of my first year in college, when people were asking me to program for them over the summer, I hadn’t programmed in so long that I wasn’t even sure I really could. I certainly did not think of myself as a particularly good programmer.

Ironic, considering Hardy writes that

Perhaps, after spending so much time not programming, the blinders had worn off. Or perhaps it was the reverse: that I had to convince myself that I was good at what I was doing now, and, since that thing was not programming, by extension, that I was not very good at programming.

Whatever the reason, I looked upon the task of actually having to program for three months with uncertainty and trepidation. For days, if I recall correctly, I dithered. Thinking myself incapable of serious programming, I thought to wait until my partner arrived and instead spend my time assisting him. But days passed and I realized it would be weeks before he would appear, and I finally decided to try to program something in the meantime.

To my shock, it went amazingly well and I have since become convinced that I’m a pretty good programmer, if lacking in most other areas. But now I find myself faced with this dilemma: it is those other areas I would much prefer to work in.

The summer before college I learned something that struck me as incredibly important and yet known by very few. It seemed clear to me that the only responsible way to live my life would be to do something that would only be done by someone who knew this thing — after all, there were few who did and many who didn’t, so it seemed logical to leave most other tasks to the majority.

I concluded that the best thing to do would be to attempt to explain this thing I’d learned to others. Any specific task I could do with the knowledge would be far outweighed by the tasks done by those I’d explained the knowledge to. It was only after I’d decided on this course of action (and perhaps this is the blinders once again) that it struck me that explaining complicated ideas was actually something I’d always loved doing and was really pretty good at.

That aside, having spent the morning reading David Foster Wallace, it is plain that I am no great writer. And so, reading Hardy, I am left wondering whether my decision is somehow irresponsible.

I am saved, I think, because it appears that Hardy’s logic to some extent parallels mine. Why is it important for the man who “can bat unusually well” to become “a professional cricketer”? It is, presumably, because those who can bat unusually well are in short supply and so the few who are gifted with that talent should do us all the favor of making use of it. If those whose “judgment of the markets is quick and sound” become cricketers, while the good batters become stockbrokers, we will end up with mediocre cricketers and mediocre stockbrokers. Better for all of us if the reverse is the case.

But this, of course, is awfully similar to the logic I myself employed. It is important for me to spend my life explaining what I’d learned because people who had learned it are in short supply — much shorter supply, in fact (or so it appears), than people who can bat well.

However, there is also an assumption hidden in that statement. It only makes sense to decide what to become based on what you can presently do if you believe that abilities are somehow granted innately and can merely be cultivated, not created in themselves. This is a fairly common view, although rarely consciously articulated (as indeed Hardy takes it for granted), but not one that I subscribe to.

Instead, it seems plausible that talent is made through practice, that those who are good batters are that way after spending enormous quantities of time batting as a kid. Mozart, for example, was the son of “one of Europe’s leading musical teachers” and said teacher began music instruction at age three. While I am plainly no Mozart, several similarities do seem apparent. My father had a computer programming company and he began showing me how to use the computer as far back as I can remember.

The extreme conclusion from the theory that there is no innate talent is that there is no difference between people and thus, as much as possible, we should get people to do the most important tasks (writing, as opposed to cricket, let’s say). But in fact this does not follow.

Learning is like compound interest. A little bit of knowledge makes it easier to pick up more. Knowing what addition is and how to do it, you can then read a wide variety of things that use addition, thus knowing even more and being able to use that knowledge in a similar manner. And so, the growth in knowledge accelerates. This is why children who get started on something at a young age, as Mozart did, grow up to have such an advantage.

And even if (highly implausibly) we were able to control the circumstances in which all children grew up so as to maximize their ability to perform the most important tasks, that still would not be enough, since in addition to aptitude there is also interest.

Imagine the three sons of a famous football player. All three are raised similarly, with athletic activity from their earliest days, and thus have an equal aptitude for playing football. Two of them pick up this task excitedly, while one, despite being good at it, is uninterested and prefers to read books. It would not only be unfair to force him to use his aptitude and play football, it would also be unwise. Someone whose heart isn’t in it is unlikely to spend the time necessary to excel.

And this, in short, is the position I find myself in. I don’t want to be a programmer. When I look at programming books, I am more tempted to mock them than to read them. When I go to programmer conferences, I’d rather skip out and talk politics than programming. And writing code, although it can be enjoyable, is hardly something I want to spend my life doing.

Perhaps, I fear, this decision deprives society of one great programmer in favor of one mediocre writer. And let’s not hide behind the cloak of uncertainty, let’s say we know that it does. Even so, I would make it. The writing is too important, the programming too unenjoyable.

And for that, I apologize.

that this is a defence which can be made by most people, since most people can do nothing at all well. But it is impregnable when it can be made without absurdity … If a man has any genuine talent he should be ready to make almost any sacrifice in order to cultivate it to the full.

Reading such comments one cannot help but apply them to oneself, and so I did. Let us eschew humility for the sake of argument and suppose that I am a great programmer. By Hardy’s suggestion, the responsible thing for me to do would be to cultivate and use my talents in that field, to spend my life being a great programmer. And that, I have to say, is a prospect I look upon with no small amount of dread.

It was not always quite this way. For quite a while programming was basically my life. And then, somehow, I drifted away. At first it was small steps — discussing programming instead of doing it, then discussing things for programmers, and then discussing other topics altogether. By the time I reached the end of my first year in college, when people were asking me to program for them over the summer, I hadn’t programmed in so long that I wasn’t even sure I really could. I certainly did not think of myself as a particularly good programmer.

Ironic, considering Hardy writes that

Good work is not done by ‘humble’ men. It is one of the first duties of a professor, for example, in any subject, to exaggerate a little both the importance of his subject and his own importance in it. A man who is always asking ‘Is what I do worthwhile?’ and ‘Am I the right person to do it?’ will always be ineffective himself and a discouragement to others. He must shut his eyes a little and think a little more of his subject and himself than they deserve. This is not too difficult: it is harder not to make his subject and himself ridiculous by shutting his eyes too tightly.

Perhaps, after spending so much time not programming, the blinders had worn off. Or perhaps it was the reverse: that I had to convince myself that I was good at what I was doing now, and, since that thing was not programming, by extension, that I was not very good at programming.

Whatever the reason, I looked upon the task of actually having to program for three months with uncertainty and trepidation. For days, if I recall correctly, I dithered. Thinking myself incapable of serious programming, I thought to wait until my partner arrived and instead spend my time assisting him. But days passed and I realized it would be weeks before he would appear, and I finally decided to try to program something in the meantime.

To my shock, it went amazingly well and I have since become convinced that I’m a pretty good programmer, if lacking in most other areas. But now I find myself faced with this dilemma: it is those other areas I would much prefer to work in.

The summer before college I learned something that struck me as incredibly important and yet known by very few. It seemed clear to me that the only responsible way to live my life would be to do something that would only be done by someone who knew this thing — after all, there were few who did and many who didn’t, so it seemed logical to leave most other tasks to the majority.

I concluded that the best thing to do would be to attempt to explain this thing I’d learned to others. Any specific task I could do with the knowledge would be far outweighed by the tasks done by those I’d explained the knowledge to. It was only after I’d decided on this course of action (and perhaps this is the blinders once again) that it struck me that explaining complicated ideas was actually something I’d always loved doing and was really pretty good at.

That aside, having spent the morning reading David Foster Wallace, it is plain that I am no great writer. And so, reading Hardy, I am left wondering whether my decision is somehow irresponsible.

I am saved, I think, because it appears that Hardy’s logic to some extent parallels mine. Why is it important for the man who “can bat unusually well” to become “a professional cricketer”? It is, presumably, because those who can bat unusually well are in short supply and so the few who are gifted with that talent should do us all the favor of making use of it. If those whose “judgment of the markets is quick and sound” become cricketers, while the good batters become stockbrokers, we will end up with mediocre cricketers and mediocre stockbrokers. Better for all of us if the reverse is the case.

But this, of course, is awfully similar to the logic I myself employed. It is important for me to spend my life explaining what I’d learned because people who had learned it are in short supply — much shorter supply, in fact (or so it appears), than people who can bat well.

However, there is also an assumption hidden in that statement. It only makes sense to decide what to become based on what you can presently do if you believe that abilities are somehow granted innately and can merely be cultivated, not created in themselves. This is a fairly common view, although rarely consciously articulated (as indeed Hardy takes it for granted), but not one that I subscribe to.

Instead, it seems plausible that talent is made through practice, that those who are good batters are that way after spending enormous quantities of time batting as a kid. Mozart, for example, was the son of “one of Europe’s leading musical teachers” and said teacher began music instruction at age three. While I am plainly no Mozart, several similarities do seem apparent. My father had a computer programming company and he began showing me how to use the computer as far back as I can remember.

The extreme conclusion from the theory that there is no innate talent is that there is no difference between people and thus, as much as possible, we should get people to do the most important tasks (writing, as opposed to cricket, let’s say). But in fact this does not follow.

Learning is like compound interest. A little bit of knowledge makes it easier to pick up more. Knowing what addition is and how to do it, you can then read a wide variety of things that use addition, thus knowing even more and being able to use that knowledge in a similar manner. And so, the growth in knowledge accelerates. This is why children who get started on something at a young age, as Mozart did, grow up to have such an advantage.

And even if (highly implausibly) we were able to control the circumstances in which all children grew up so as to maximize their ability to perform the most important tasks, that still would not be enough, since in addition to aptitude there is also interest.

Imagine the three sons of a famous football player. All three are raised similarly, with athletic activity from their earliest days, and thus have an equal aptitude for playing football. Two of them pick up this task excitedly, while one, despite being good at it, is uninterested and prefers to read books. It would not only be unfair to force him to use his aptitude and play football, it would also be unwise. Someone whose heart isn’t in it is unlikely to spend the time necessary to excel.

And this, in short, is the position I find myself in. I don’t want to be a programmer. When I look at programming books, I am more tempted to mock them than to read them. When I go to programmer conferences, I’d rather skip out and talk politics than programming. And writing code, although it can be enjoyable, is hardly something I want to spend my life doing.

Perhaps, I fear, this decision deprives society of one great programmer in favor of one mediocre writer. And let’s not hide behind the cloak of uncertainty, let’s say we know that it does. Even so, I would make it. The writing is too important, the programming too unenjoyable.

And for that, I apologize.

THE ATTRACTION OF THE CENTER (AARON SWARTZ)

“Centrism” is the tendency to see two different beliefs and attempt to split the difference between them. The reason why it’s a bad idea should be obvious: truth is independent of our beliefs, no less than any other partisans, centrists ignore evidence in favor of their predetermined ideology.

So what’s the attraction? First, it requires little thought: arguing for a specific position requires collecting evidence and arguing for it. Centrism, simply requires repeating some of what A is saying and some of what B is saying and mixing them together. Centrists often don’t even seem to care if the bits they take contradict each other.

Second, it’s somewhat inoffensive. Taking a strong stand on A or B will unavoidably alienate some. But being a centrist, one can still maintain friends on both sides, since they will find at least some things that you espouse to be agreeable with their own philosophies.

Third, it makes it easier to suck up to those in charge, because the concept of the “center” can easily move along with shifts in power. A staunch conservative will have to undergo a major change of political philosophy to get a place in liberal administration. A centrist can simply espouse a few more positions from the conservatives and a few less from the liberals and fit in just fine. This criteria explains why centrists are so prevalent in the pundit class (neither administration is tempted to really force them out) and why so many “centrist” pundits espouse mostly conservative ideas these days (the conservatives are in power).

Fourth, despite actually being a servant of those in power, centrism gives one the illusion of actually being a serious, independent thinker. “People on the right and on the left already know what they’re going to say on every issue,” they might claim, “but we centrists make decisions based on the situation.” (This excuse was recently used in a fundraising letter by The New Republic.) Of course, the “situation” that’s used to make these decisions is simply who’s currently in power, as discussed above, but that part is carefully omitted.

Fifth, it appeals to the public. There’s tremendous dissatisfaction among the public with the government and our system of politics. Despite being precisely in the middle of this corrupt system, centrists can claim that they’re actually “independents” and “disagree with both the left and the right”. They can denounce “extremism” (which isn’t very popular) and play the “moderate”, even when their positions are extremely far from what the public believes or what the facts say.

Together, these reasons combine to make centrism an especially attractive place to be in American politics. But the disease is far from limited to politics. Journalists frequently suggest the truth lies between the two opposing sources they’ve quoted. Academics try to distance themselves from policy positions proposed by either party. And, perhaps worst of all, scientists try to split the difference between two competing theories.

Unfortunately for them, neither the truth nor the public necessarily lies somewhere in the middle. Fortunately for them, more valuable rewards do.

Exercise for the reader: What’s the attraction of “contrarianism”, the ideology subscribed to by online magazines like Slate?

So what’s the attraction? First, it requires little thought: arguing for a specific position requires collecting evidence and arguing for it. Centrism, simply requires repeating some of what A is saying and some of what B is saying and mixing them together. Centrists often don’t even seem to care if the bits they take contradict each other.

Second, it’s somewhat inoffensive. Taking a strong stand on A or B will unavoidably alienate some. But being a centrist, one can still maintain friends on both sides, since they will find at least some things that you espouse to be agreeable with their own philosophies.

Third, it makes it easier to suck up to those in charge, because the concept of the “center” can easily move along with shifts in power. A staunch conservative will have to undergo a major change of political philosophy to get a place in liberal administration. A centrist can simply espouse a few more positions from the conservatives and a few less from the liberals and fit in just fine. This criteria explains why centrists are so prevalent in the pundit class (neither administration is tempted to really force them out) and why so many “centrist” pundits espouse mostly conservative ideas these days (the conservatives are in power).

Fourth, despite actually being a servant of those in power, centrism gives one the illusion of actually being a serious, independent thinker. “People on the right and on the left already know what they’re going to say on every issue,” they might claim, “but we centrists make decisions based on the situation.” (This excuse was recently used in a fundraising letter by The New Republic.) Of course, the “situation” that’s used to make these decisions is simply who’s currently in power, as discussed above, but that part is carefully omitted.

Fifth, it appeals to the public. There’s tremendous dissatisfaction among the public with the government and our system of politics. Despite being precisely in the middle of this corrupt system, centrists can claim that they’re actually “independents” and “disagree with both the left and the right”. They can denounce “extremism” (which isn’t very popular) and play the “moderate”, even when their positions are extremely far from what the public believes or what the facts say.

Together, these reasons combine to make centrism an especially attractive place to be in American politics. But the disease is far from limited to politics. Journalists frequently suggest the truth lies between the two opposing sources they’ve quoted. Academics try to distance themselves from policy positions proposed by either party. And, perhaps worst of all, scientists try to split the difference between two competing theories.

Unfortunately for them, neither the truth nor the public necessarily lies somewhere in the middle. Fortunately for them, more valuable rewards do.

Exercise for the reader: What’s the attraction of “contrarianism”, the ideology subscribed to by online magazines like Slate?

THE HAWKING PARADOX - BBC HORIZON

Series exploring topical scientific issues examines Professor Stephen Hawking's most controversial theory and possibly his greatest mistake.

For thirty years the most famous scientist in the world defended an extraordinary idea, an idea some claimed would undermine the whole of science. It was called the information paradox and it led one opponent to dub Hawking 'the most stubborn man in the universe'. But finally Hawking had to admit that he'd been wrong all along. Now, as he nears the end of his extraordinary career, Hawking's scientific legacy is being called into question like never before.

For a year Horizon filmed behind the scenes with Hawking as he struggled to finish what many thought was going to be his last scientific paper. If he succeeded he would potentially end his career on a high, confirming his status as one of the great figures in physics. But the odds were against him, as his physical health continued to decline.

This is an extraordinary story of one man's defiance of disability and his peers. It is a story that ranges from the beginning of the universe, which Hawking explored, to the intensive care unit of Addenbrookes, where he was taken and was critically ill for three months. On his hospital bed he had an insight which he hoped would form the basis of his latest comeback.

sexta-feira, 29 de dezembro de 2017

THE WORLD OF M. C. ESCHER

Seguindo com os meus estudos sobre Escher, selecionei as minhas obras favoritas do livro "The World of M. C. Escher".

ALGORITMOS DAS REDE SOCIAIS PROMOVEM PRECONCEITO E DESIGUALDADE, DIZ MATEMÁTICA DE HARVARD

Eles estão por toda parte. Nos formulários que preenchemos para vagas de emprego. Nas análises de risco a que somos submetidos em contratos com bancos e seguradoras. Nos serviços que solicitamos pelos nossos smartphones. Nas propagandas e nas notícias personalizadas que abarrotam nossas redes sociais. E estão aprofundando o fosso da desigualdade social e colocando em risco as democracias.

Definitivamente, não é com entusiasmo que a americana Cathy O'Neil enxerga a revolução dos algoritmos, sistemas capazes de organizar uma quantidade cada vez mais impressionante de informações disponíveis na internet, o chamado Big Data.

Matemática com formação em Harvard e Massachussetts Institute of Technology (MIT), duas das mais prestigiadas universidades do mundo, ela abandonou em 2012 uma bem-sucedida carreira no mercado financeiro e na cena das startups de tecnologia para estudar o assunto a fundo.

Quatro anos depois, publicou o livro Weapons of Math Destruction (Armas de Destruição em Cálculos, em tradução livre, um trocadilho com a expressão "armas de destruição em massa" em inglês) e tornou-se uma das vozes mais respeitadas no país sobre os efeitos colaterais da economia do Big Data.

A obra é recheada de exemplos de modelos matemáticos atuais que ranqueiam o potencial de seres humanos como estudantes, trabalhadores, criminosos, eleitores e consumidores. Segundo a autora, por trás da aparente imparcialidade desses sistemas, escondem-se critérios nebulosos que agravam injustiças.

É o caso dos seguros de automóveis nos Estados Unidos. Motoristas que nunca tomaram uma multa sequer, mas que tinham restrições de crédito por morarem em bairros pobres, pagavam valores consideravelmente mais altos do que aqueles com facilidade de crédito, mas já condenados por dirigirem embriagados. "Para a seguradora, é um ganha-ganha. Um bom motorista com restrição de crédito representa um risco baixo e um retorno altíssimo", exemplifica.

Confira abaixo os principais trechos da entrevista:

BBC Brasil - Há séculos pesquisadores analisam dados para entender padrões de comportamento e prever acontecimentos. Qual é novidade trazida pelo Big Data?

Cathy O'Neil - O diferencial do Big Data é a quantidade de dados disponíveis. Há uma montanha gigantesca de dados que se correlacionam e que podem ser garimpados para produzir a chamada "informação incidental". É incidental no sentido de que uma determinada informação não é fornecida diretamente - é uma informação indireta. É por isso que as pessoas que analisam os dados do Twitter podem descobrir em qual político eu votaria. Ou descobrir se eu sou gay apenas pela análise dos posts que curto no Facebook, mesmo que eu não diga que sou gay.

Definitivamente, não é com entusiasmo que a americana Cathy O'Neil enxerga a revolução dos algoritmos, sistemas capazes de organizar uma quantidade cada vez mais impressionante de informações disponíveis na internet, o chamado Big Data.

Matemática com formação em Harvard e Massachussetts Institute of Technology (MIT), duas das mais prestigiadas universidades do mundo, ela abandonou em 2012 uma bem-sucedida carreira no mercado financeiro e na cena das startups de tecnologia para estudar o assunto a fundo.

Quatro anos depois, publicou o livro Weapons of Math Destruction (Armas de Destruição em Cálculos, em tradução livre, um trocadilho com a expressão "armas de destruição em massa" em inglês) e tornou-se uma das vozes mais respeitadas no país sobre os efeitos colaterais da economia do Big Data.

A obra é recheada de exemplos de modelos matemáticos atuais que ranqueiam o potencial de seres humanos como estudantes, trabalhadores, criminosos, eleitores e consumidores. Segundo a autora, por trás da aparente imparcialidade desses sistemas, escondem-se critérios nebulosos que agravam injustiças.

É o caso dos seguros de automóveis nos Estados Unidos. Motoristas que nunca tomaram uma multa sequer, mas que tinham restrições de crédito por morarem em bairros pobres, pagavam valores consideravelmente mais altos do que aqueles com facilidade de crédito, mas já condenados por dirigirem embriagados. "Para a seguradora, é um ganha-ganha. Um bom motorista com restrição de crédito representa um risco baixo e um retorno altíssimo", exemplifica.

Confira abaixo os principais trechos da entrevista:

BBC Brasil - Há séculos pesquisadores analisam dados para entender padrões de comportamento e prever acontecimentos. Qual é novidade trazida pelo Big Data?

Cathy O'Neil - O diferencial do Big Data é a quantidade de dados disponíveis. Há uma montanha gigantesca de dados que se correlacionam e que podem ser garimpados para produzir a chamada "informação incidental". É incidental no sentido de que uma determinada informação não é fornecida diretamente - é uma informação indireta. É por isso que as pessoas que analisam os dados do Twitter podem descobrir em qual político eu votaria. Ou descobrir se eu sou gay apenas pela análise dos posts que curto no Facebook, mesmo que eu não diga que sou gay.

A questão é que esse processo é cumulativo. Agora que é possível descobrir a orientação sexual de uma pessoa a partir de seu comportamento nas redes sociais, isso não vai ser "desaprendido". Então, uma das coisas que mais me preocupam é que essas tecnologias só vão ficar melhores com o passar do tempo. Mesmo que as informações venham a ser limitadas - o que eu acho que não vai acontecer - esse acúmulo de conhecimento não vai se perder.

BBC Brasil - O principal alerta do seu livro é de que os algoritmos não são ferramentas neutras e objetivas. Pelo contrário: eles são enviesados pelas visões de mundo de seus programadores e, de forma geral, reforçam preconceitos e prejudicam os mais pobres. O sonho de que a internet pudesse tornar o mundo um lugar melhor acabou?

O'Neil - É verdade que a internet fez do mundo um lugar melhor em alguns contextos. Mas, se colocarmos numa balança os prós e os contras, o saldo é positivo? É difícil dizer. Depende de quem é a pessoa que vai responder. É evidente que há vários problemas. Só que muitos exemplos citados no meu livro, é importante ressaltar, não têm nada a ver com a internet. As prisões feitas pela polícia ou as avaliações de personalidade aplicadas em professores não têm a ver estritamente com a internet. Não há como evitar que isso seja feito, mesmo que as pessoas evitem usar a internet. Mas isso foi alimentado pela tecnologia de Big Data.

Por exemplo: os testes de personalidade em entrevistas de emprego. Antes, as pessoas se candidatavam a uma vaga indo até uma determinada loja que precisava de um funcionário. Mas hoje todo mundo se candidata pela internet. É isso que gera os testes de personalidade. Existe uma quantidade tão grande de pessoas se candidatando a vagas que é necessário haver algum filtro.

BBC Brasil - Qual é o futuro do trabalho sob os algoritmos?

O'Neil - Testes de personalidade e programas que filtram currículos são alguns exemplos de como os algoritmos estão afetando o mundo do trabalho. Isso sem mencionar os algoritmos que ficam vigiando as pessoas enquanto elas trabalham, como é o caso de professores e caminhoneiros. Há um avanço da vigilância. Se as coisas continuarem indo do jeito como estão, isso vai nos transformar em robôs.

Mas eu não quero pensar nisso como um fato inevitável - que os algoritmos vão transformar as pessoas em robôs ou que os robôs vão substituir o trabalho dos seres humanos. Eu não quero admitir isso. Isso é algo que podemos decidir que não vai acontecer. É uma decisão política. Essa ideia de que os robôs vão substituir o trabalho humano é muito fatalista. É preciso reagir e mostrar que essa é uma batalha política. O problema é que estamos tão intimidados pelo avanço dessas tecnologias que sentimos que não há como lutar contra.

BBC Brasil - E no caso das companhias de tecnologia como a Uber? Alguns estudiosos usam o termo "gig economy" (economia de "bicos") para se referir à organização do trabalho feita por empresas que utilizam algoritmos.

O'Neil - Esse é um ótimo exemplo de como entregamos o poder a essas empresas da gig economy, como se fosse um processo inevitável. Certamente, elas estão se saindo muito bem na tarefa de burlar legislações trabalhistas, mas isso não quer dizer que elas deveriam ter permissão para agir dessa maneira. Essas companhias deveriam pagar melhores remunerações e garantir melhores condições de trabalho.

No entanto, os movimentos que representam os trabalhadores ainda não conseguiram assimilar as mudanças que estão ocorrendo. Mas essa não é uma questão essencialmente algorítmica. O que deveríamos estar perguntando é: como essas pessoas estão sendo tratadas? E, se elas não estão sendo bem tratadas, deveríamos criar leis para garantir isso.

Eu não estou dizendo que os algoritmos não têm nada a ver com isso - eles têm, sim. É uma forma que essas companhias usam para dizer que elas não podem ser consideradas "chefes" desses trabalhadores. A Uber, por exemplo, diz que os motoristas são autônomos e que o algoritmo é o chefe. Esse é um ótimo exemplo de como nós ainda não entendemos o que se entende por "responsabilidade" no mundo dos algoritmos. Essa é uma questão em que venho trabalhando há algum tempo: que pessoas vão ser responsabilizadas pelos erros dos algoritmos?

BBC Brasil - No livro você argumenta que é possível criar algoritmos para o bem - o principal desafio é garantir transparência. Porém, o segredo do sucesso de muitas empresas é justamente manter em segredo o funcionamento dos algoritmos. Como resolver a contradição?

O'Neil - Eu não acho que seja necessária transparência para que um algoritmo seja bom. O que eu preciso saber é se ele funciona bem. Eu preciso de indicadores de que ele funciona bem, mas isso não quer dizer que eu necessite conhecer os códigos de programação desse algoritmo. Os indicadores podem ser de outro tipo - é mais uma questão de auditoria do que de abertura dos códigos.

A melhor maneira de resolver isso é fazer com que os algoritmos sejam auditados por terceiros. Não é recomendável confiar nas próprias empresas que criaram os algoritmos. Precisaria ser um terceiro, com legitimidade, para determinar se elas estão operando de maneira justa - a partir da definição de alguns critérios de justiça - e procedendo dentro da lei.

BBC Brasil - Recentemente, você escreveu um artigo para o jornal New York Times defendendo que a comunidade acadêmica participe mais dessa discussão. As universidades poderiam ser esse terceiro de que você está falando?

O'Neil - Sim, com certeza. Eu defendo que as universidades sejam o espaço para refletir sobre como construir confiabilidade, sobre como requerer informações para determinar se os algoritmos estão funcionando.

BBC Brasil - Quando vieram a público as revelações de Edward Snowden de que o governo americano espionava a vida das pessoas através da internet, muita gente não se surpreendeu. As pessoas parecem dispostas a abrir mão da sua privacidade em nome da eficiência da vida virtual?

O'Neil - Eu acho que só agora estamos percebendo quais são os verdadeiros custos dessa troca. Com dez anos de atraso, estamos percebendo que os serviços gratuitos na internet não são gratuitos de maneira alguma, porque nós fornecemos nossos dados pessoais. Há quem argumente que existe uma troca consentida de dados por serviços, mas ninguém faz essa troca de forma realmente consciente - nós fazemos isso sem prestar muita atenção. Além disso, nunca fica claro para nós o que realmente estamos perdendo.

Mas não é pelo fato de a NSA (sigla em inglês para a Agência de Segurança Nacional) nos espionar que estamos entendendo os custos dessa troca. Isso tem mais a ver com os empregos que nós arrumamos ou deixamos de arrumar. Ou com os benefícios de seguros e de cartões de crédito que nós conseguimos ou deixamos de conseguir. Mas eu gostaria que isso estivesse muito mais claro.

No nível individual ainda hoje, dez anos depois, as pessoas não se dão conta do que está acontecendo. Mas, como sociedade, estamos começando a entender que fomos enganados por essa troca. E vai ser necessário um tempo para saber como alterar os termos desse acordo.

BBC Brasil - O último capítulo do seu livro fala sobre a vitória eleitoral de Donald Trump e avalia como as pesquisas de opinião e as redes sociais influenciaram na corrida à Casa Branca. No ano que vem, as eleições no Brasil devem ser as mais agitadas das últimas três décadas. Que conselho você daria aos brasileiros?

O'Neil - Meu Deus, isso é muito difícil! Está acontecendo em todas as partes do mundo. E eu não sei se isso vai parar, a não ser que fechem o Facebook - o que, a propósito, eu sugiro que façamos. Agora, falando sério: as campanhas políticas na internet devem ser permitidas, mas não deveriam ser permitidos anúncios personalizados, customizados - ou seja, todo mundo deveria receber os mesmos anúncios. Eu sei que essa ainda não é uma proposta realista, mas acho que deveríamos pensar grande porque esse problema é grande. E eu não consigo pensar em outra maneira de resolver essa questão.

É claro que isso seria um elemento de um conjunto maior de medidas porque nada vai impedir pessoas idiotas de acreditar no que elas querem acreditar - e de postar sobre isso. Ou seja, nem sempre é um problema do algoritmo. Às vezes, é um problema das pessoas mesmo. O fenômeno das fake news é um exemplo. Os algoritmos pioram a situação, personalizando as propagandas e amplificando o alcance, porém, mesmo que não existisse o algoritmo do Facebook e que as propagandas políticas fossem proibidas na internet, ainda haveria idiotas disseminando fake news que acabariam viralizando nas redes sociais. E eu não sei o que fazer a respeito disso, a não ser fechar as redes sociais.

Eu tenho três filhos, eles têm 17, 15 e 9 anos. Eles não usam redes sociais porque acham que são bobas e eles não acreditam em nada do que veem nas redes sociais. Na verdade, eles não acreditam em mais nada - o que também não é bom. Mas o lado positivo é que eles estão aprendendo a checar informações por conta própria. Então, eles são consumidores muito mais conscientes do que os da minha geração. Eu tenho 45 anos, a minha geração é a pior. As coisas que eu vi as pessoas da minha idade compartilhando após a eleição de Trump eram ridículas. Pessoas postando ideias sobre como colocar Hilary Clinton na presidência mesmo sabendo que Trump tinha vencido. Foi ridículo. A esperança é ter uma geração de pessoas mais espertas.

Assinar:

Comentários (Atom)